I studied yoga for several years before I really became interested in the history of the practice. Ultimately, I figured it was pretty straightforward. Yogis have passed on teachings for many thousands of years and that brings the practice to us today. Right? Well not quite..

After Mark Singleton published Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice there was a mixed response of denial, and further exploration, within the yoga community about the roots of this seemingly ancient practice. If you’re interested in learning more about the beginnings of the physical asana practice we use today I would highly recommend this book. I’ve also had the pleasure of studying with Chip Hartranft who has studied the history of this ancient practice in depth. His book The Yoga-Sutra of Patanjali: A New Translation with Commentary is a thorough translation of the Yoga Sutras I would recommend.

A History of Yoga

When we speak of yoga we’re actually referring to a plethora of paths that have changed and evolved over time. For example, Hindu and Buddhist traditions have been greatly influenced by yogic teaching. Even the systems of Buddhism and Hinduism do not need to be confined to the narrow definitions of religion. Both these traditions are simply manifestations of larger cultural movements. They both grew from the development of spiritual practices first catalyzed by ancient yogic teachings.

Throughout yoga’s history, teachings have been passed on orally, memorized, and recited countless times. The early yogis followed teachings dating all the way back to the most ancient of texts; the vedas. But despite the multitude of approaches yoga has offered throughout the ages, yogis have seemed to agree, for the most part, on a few basic principles.

At its most pith distillation, yogis have recognized that this human existence is illusory and we need to wake up to reality for our true liberation. This is the purpose of yoga.

~ 3000 – 1500 B.C.E Information came through a priest class (Brahmins). Sacrifices and visions were important cornerstones of the culture that divided those who could access higher spiritual powers and lay people who made up the rest of society. The rig vedas are a series of 1028 hymns in Sanskrit about meditation and various practices that were used and created by seers and saints during this time.

~ 800 B.C.E Much of the wisdom of the vedas was slowly lost. Instead, rituals led by Brahmin priests left lay people longing for their own personal connection to the divine. A growing number of seekers began to question the status quo and leave their families, jobs, and communities behind. Many of these seekers followed Jainism and practiced disciplines (tapas) in search of answers to age old questions related to spirituality and meaning. Many practices involved strict renunciation and ethics.

By turning away from the mainstream form of religious worship, ruled by the Brahmin priests, these early yogis were considered radicals. These yogis developed practices that encouraged deep states of jhana (meditative absorption) and they emphasized contact with a self that is boundless and intimately connected with the totality of creation. The early Upanishads (lit. sitting near ones teacher) are recorded from approximately 1500-200 B.C.E

~ 500 B.C.E Siddhartha Gotama, a young son of a powerful leader, starts questioning the meaning of his own life through a series of auspicious events that demonstrate the fragility of life. Eventually he too leaves his family, takes up robes, and rejects conventional life for the spiritual path. The spiritual seekers he joins are now becoming a strong voice within the social and political structure in India.

Siddhartha practices for some time but eventually leaves the harsh restrictions of the ascetic life. He sees that even though he and his colleagues are able to reach great states of bliss through specific practices they always return to this reality which is full of dhukka (suffering). One day Siddhartha accepts a bowl of rice milk from a young woman and resolves to stay under the bodhi tree until his full enlightenment. He attains enlightenment not long after and becomes known as “the awake one” or the Buddha.

The Buddha goes on to teach for approximately 60 years. His teachings are similar to the traditions he was practicing when he became enlightened with one important distinction. The Buddha emphasized that focusing on the impermanent nature of all reality including the self leads to full and complete liberation. Some of the Buddha’s key teachings include the four noble truths and the noble eight fold path. The Buddha’s teachings travelled across the globe and morphed into the many traditions we see today.

~ 300 B.C.E One of the last of the early Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, is created and taught. It contains no ritualistic ideas and instead espouses deeper spiritual teachings. The Vedas and the Upanishads are considered direct knowledge from an intuitive sage. All teachings after this time are considered sutras which are based more on tradition and not on inspired discovery of a highly realized being.

~ 200 B.C.E The yoga sutras of Patanjali are created somewhere between 200 B.C.E and 200 A.D. There is debate about whether Patanjali was one man or whether the sutras are actually a collection from various teachers and students.

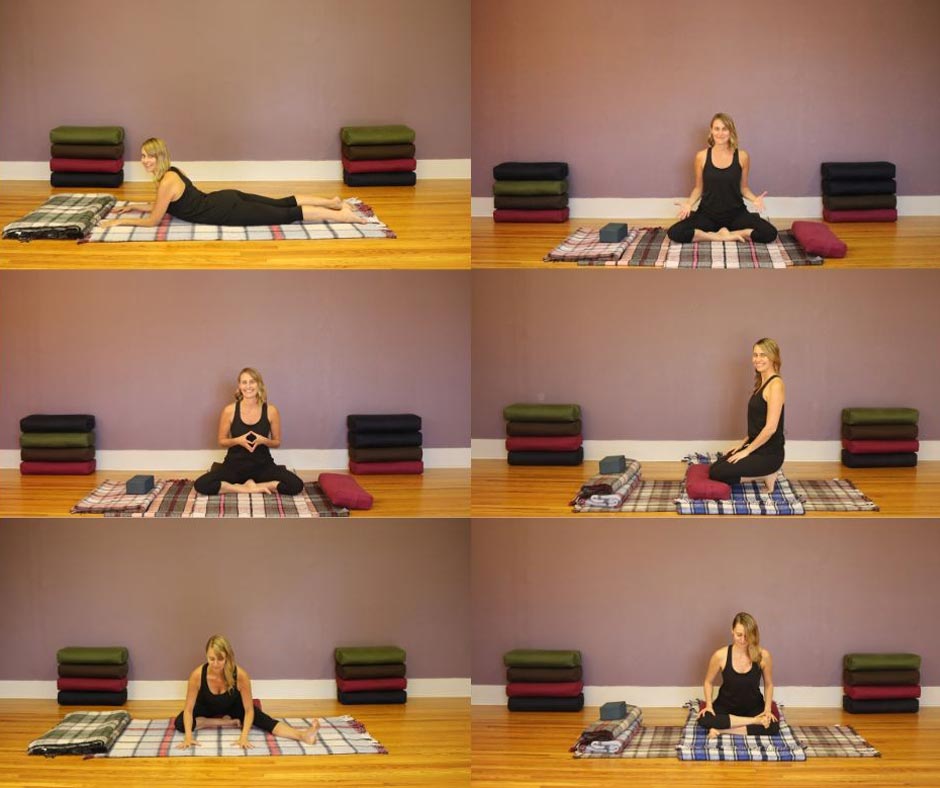

The yoga sutras contain the outline of the eightfold path of yoga (sometimes referred to as “ashtanga yoga” or “royal yoga”): Yamas (ethical conduct) Niyamas (inner integrity) Asana (posture) Pranayama (breath manipulation) Pratyahara (withdrawal of senses) Dharana (concentration) Dhyana (meditation) Samadhi (unity consciousness) With a foundation of inner and outer ethical guidelines the yogi sits in meditation through asana (literally seat) and develops greater states through the last limbs outlined above. The sutras draw on the teachings of the yogis and sages that came before this time including the emphasis related to meditative practice taught by the Buddha.

~ 800 – 1100 C.E Up to this point both Hindu and Buddhist yoga schools focused on the true nature of reality and how to find inner freedom through specific practices. However, through the recognition that manifest reality was ultimately impermanent and full of suffering, an attitude developed that was divorced from, if not averse, to worldly things such as women, the body, and sexuality. Because of this, tantra arose, a new kind of practice led primarily by lay people, which used daily existence as a kind of vehicle for transformation.

During this time practitioners mapped intricate details of the subtle energetic channels or nadis. They codified the teachings of kundalini, purification, and the bandhas. They also developed greater understandings related to breaking through psychological, emotional, and energetic blocks. Out of this milieu, Hatha yoga emerged, and with it, a number of influential texts. The most popular being the Hatha Yoga Pradapika.

The emphasis Hatha yoga places on complicated bodily postures, purification practices, and breath work connect it to the tantric tradition. However, Hatha yogis distanced themselves from tantra as the tantric revolution had gained a bad reputation due to the many unsightly and unconventional practices it utilized, such as practice in charnel grounds, or its close connection to deviance from sexual norms. During this same time the tantric practices of body postures and breath work spread to Tibet helping to inform what is now a school of Buddhism called Vajrayana.

Early 1900’s C.E As Indian national pride rose during the early part of the twentieth century the search to create a system of health that would replace the imported British YMCA became a priority for nationalists. Dedicated yogis started combining ancient yogic teachings with systems of European gymnastics. These new hybrid offerings were presented within a standardized context which was thought to be more palatable to mainstream modern society.

T. Krishnamacharya, B.K.S Iyengar, and Sri Satchinanda all popularized this form of yoga further by teaching various influential people and westerners. These westerners often traveled back home and spread the practices further. The blending of the fitness and personal development world and western sensibilities and values, with the more ancient practices of meditation and breath work, has brought us the practice of yoga many of us use today.

Just like culture, yoga is not static. It is a living breathing process deeply informed by centuries of spiritual seekers and practitioners. The possibilities of how this ancient and sacred practice will evolve are yet to be discovered.